The AEC knew the risks of dispersing radioactive materials in the air as early as 1950 and was studying the phenomena. ![]()

Uncategorized

No Excuses

The Panama Connection

A Member of the Club

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch trots out a nuke industry shill to defend the latest missteps by of the EPA at West Lake Landfill

On April 2, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the EPA had finally admitted that radioactive waste is migrating beyond the boundaries of the West Lake Landfill Superfund site. That would normally be a cause for praise. The remainder of the story, however, staunchly defended the agency’s less-than-sterling record mainly by downplaying the significance of its latest self-professed lapses.

The latest findings by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources show contamination above federal permissible levels. The findings contradict repeated denials by former Region 7 Director Karl Brooks and others even though publicly available EPA documents have confirmed the movement of the contamination off site in the past. The lack of candor by the EPA raises questions about the agency’s overall characterization of West Lake.

But have no fear.

To assure the public that all is well at the radioactively-contaminated site in North St. Louis County, reporter Jacob Barker quotes Bill Miller of the University of Missouri Research Reactor.

Referring to the newly discovered radioactive soil, Barker reported that Miller’s calculations indicate “a person would need to eat 20 pounds of dirt to be exposed to as much radiation as the average American gets annually from naturally occurring radon.”

Miller’s calculation is presented without rebuttal. The obvious inference is that Miller is a scientific voice of reason and that his viewpoint is objective.

A closer look at Miller’s background hints otherwise.

Miller’s employer, the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR), is inextricably tied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Department of Energy. The DOE is one of the responsible parties for the cleanup of West Lake. Moreover, before it became a responsible party the DOE was in charge of the site prior to inexplicably handing it over to the EPA in 1990.

So the expert cited by the Post-Dispatch is not objective. Instead, he is an advocate of the mammoth nuclear industry, which is subsidized by the federal government. Miller’s job depends on maintaining the status quo in regard to all things relating to federal nuclear policy.

Signs of Miller’s bias don’t stop there, however.

MURR depends on the nuclear industry to stay in business. For example, its first customer in 1967 was the Mallinckrodt Nuclear Corp. Mallinckrodt is the company that created the nuclear waste that is scattered around the St. Louis area, including the West Lake Landfill. The company began processing uranium for the Manhattan Project in 1942. Mallinckrodt continued its uranium work during the Cold War for the Atomic Energy Commission until 1967.

More recently, Mallinckrodt has employed the services of health physicists that formerly worked for MURR. MURR in essence acts a de facto training ground for Mallinckrodt. In short, there is a revolving door between private industry and the university research reactor.

By presenting Miller’s opinion without providing its readers with details of his employer, the Post-Dispatch misled the public. The question is did the newspaper do this intentionally.

The Gravity of the Situation

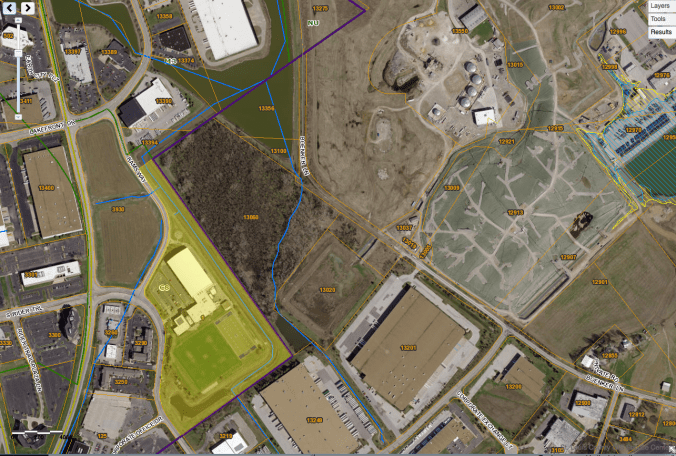

The Rams former practice field is perched precariously on the edge of an uncontrolled nuclear waste dump.

Under the terms of its agreement with the St. Louis Regional Sports Authority, the newly relocated Los Angeles Rams have the opportunity to buy the football team’s former 27-acre practice facility in Earth City for $1. Late last month, the sports authority went to court to keep the land grab from happening. The property once had an assessed value of $19 million.

But its current value is likely far less.

That’s because Rams Park is directly adjacent to the West Lake Landfill Superfund site. A portion of that site contains an underground fire that is getting closer to radioactive waste that was dumped there illegally in 1973. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources and EPA have been watching this slow burn occur for five years and haven’t taken steps to deal with it yet. As a result, the toxic stench at the site has been besieging nearby residents for just as long.

There is another dilemma at West Lake, however, which is the opposite of fire. Chemical and radioactive waste continues to seep into the groundwater. The location of the landfill makes the situation more dire because it sits in the Missouri River floodplain several miles from the confluence with the Mississippi, which supplies water to the city of St. Louis.

Surface water is no less a concern. The training facility is downhill from the landfill. Testing conducted in 1991 found radioactive contamination in Earth City. The findings of that report were later disputed, leaving the question unresolved.

Last week, the EPA admitted what it had already determined years ago. Radioactive thorium has escaped the confines of the Superfund site at another location. The migration is on the perimeter of the landfill in the vicinity of one of the hundreds of businesses in Earth City.

The development, which is protected by a 2.6 mile levee that is overseen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is comprised of four separate business parks totaling more than 1,800 acres. An estimated 22,000 people work here. The business conducted in Earth City drives a sizable chunk of North St. Louis County’s economy. Its market value is $1.2 billion.

With more than a billion dollars on the line, real estate and business interests would probably prefer to forget about this mess, to act like nothing is wrong. They’ve been denying the problem for a long time. It’s like a sickness that nobody wants to admit they have. But it never goes away, and ignoring the growing symptoms only makes matters worse.

Wealthy landowners, lords of the local press, powerful corporations, revenue hungry governments , influential private and public institutions — all have a stake in Earth City and its future. That future is at best uncertain.

The satellite images of Earth City resemble Venice. Canals crisscross the district, acting as an integral part of the drainage system. Looking down on the backside of the landfill it’s apparent that the sloping ground abuts one of these waterways. The view from on high also shows what appears to be a former cess pool next to the Rams’ former practice field.

The spring rains will soon fall on the Missouri floodplain; and once again rivers will rise, and gravity will cause water to wash inevitably into the canals of Earth City.

The Regional Sports Authority has a piece of real estate it would like to sell you.

Caveat emptor.

What Nobody is Saying

Notes obtained by StlReporter Say West Lake Nuke Waste is Present at Previously Undisclosed Locations.

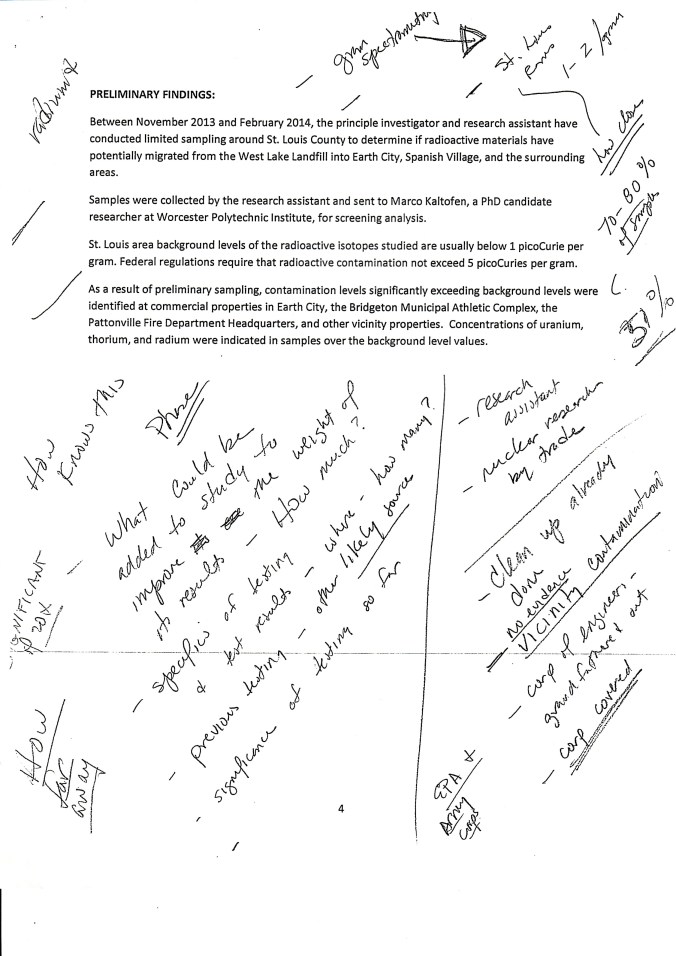

Notes on the preliminary findings of independent sampling conducted in 2013 and 2014 indicate that above background levels of radioactive contamination were discovered at multiple locations in St. Louis County, including the Bridgeton Fire Protection District.

Neither those involved in the testing or the regulatory agencies involved in monitoring the West Lake Superfund site have disclosed the locations of the contamination, leaving the public at large in the dark.

The First Secret City Screening

Please join us for a free screening of The First Secret City.

March 12, 2016 – 3pm

St. Matthews Church

2613 Potomac St.

St. Louis, MO 63118

Donations for Just Moms STL accepted. Presented by The Missouri Accountability Project, Just Moms STL, and Stella Maris Productions.

With speakers after the film, and a special musical performance from Kellie Everett of the Southwest Watson Sweethearts who will play her song “The Bridgeton Fire” before the movie. Thank you to protectionist, Raven Fox with Radiant Studio Works, and James Bratten skinnyd.com for his work on promotional flyer.

Under the Cloud

Author Richard Miller spent years uncovering the harm caused to Americans by nuclear fallout from atmospheric testing

first published in the Riverfront Times in the 1990s.

BY C.D. STELZER

The image cast by the overhead projector showed a grainy snapshot of a boy with a crew cut crouched next to a tail-wagging dog. In the faded background, a pick-up truck could be seen parked next to a modest frame house. The time was 1955; the place Paris, Mo.

The bucolic setting could not have been more deceptive. When the spring rains fell that year, they permanently changed the lives of many residents of the small town in the northeast corner of the state, as they did countless other lives across the continent. But unlike the havoc reeked by floods or other natural disasters, the damage to humanity could not be immediately measured. At the time, few people knew anything about the effects of exposure to radioactive fallout. Nuclear weapons research, propelled by the arms race and the ensuing hysteria over national security, proceeded unimpeded. Between 1951 and 1963 more than one hundred above-ground atomic bombs blasts were detonated by the federal government at its Nev ada Test Site.

Richard L. Miller — the youngster in the photograph — has spent much of his adult life learning of the consequences of that nuclear atmospheric testing during the Cold War.

Last Saturday, the 50-year-old author displayed the black-and-white image from his childhood along with photographs of nuclear explosions at a conference of the National Association of Radiation Survivors, which convened at the Henry VIII Hotel on North Lindbergh Boulevard. Miller, who wrote Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing, feels both vindicated and disturbed by the findings of a recently released National Cancer Institute (NCI) study on the dangers of nuclear fallout.

“First and foremost, … it’s an admission by the government that they dose d the entire United States with fallout,” Miller told the audience. The NCI study made public in August took almost a decade-and-a-half to complete. It concludes that 10,000 to 75,000 people, who were exposed to high levels of fallout of as children, may contract thyroid cancer as a result.

The wind, rain and weather dispersed the isotope randomly across large sections of the U.S. and Canada, after the detonation of experimental atomic bombs blasts. Most of the children were exposed to the fallout, Iodine-131, by drinking contaminated milk.

Despite the belated confession by the federal government, Miller criticized the NCI report for excluding relevant data, which if taken into account would increase the potential health problems caused by the fallout. “There are two hundred other isotopes,” he says, “isotopes that can cause cancer in other parts of the body, including bone cancer and leukemia.” None of the those elements were factored into the study, however.

Miller found another oversight. “They did not include all the maps.” Miller caught the omission by comparing NCI data available on Internet with copies of 1959 Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and National Weather Service documents he had tucked away in his closet. Interestingly, the fal lout from the14 nuclear blasts excluded from the NCI study, all show fallout crossing into Canada, according to Miller.

“The NCI’s maps, to be charitable, are not very good. They don’t give the same amount of information that the originals do,” says Mi ller. “They spent 15 years working on this thing. … You would think that they would have the very best computer technology available to enhance the quality of the images.”

When Miller recently asked the Missouri Department of Health whether it had correlated data on fallout with any other forms of cancer other than the type that attack the thyroid gland, the agency said it had not. Regarding thyroid cancer, the health department claimed that based on available data there appeared to be no increase in the Missouri counties, Miller says.

Miller doesn’t agree with either finding. In his opinion, the state like its federal counterpart is continuing to exclude data that indicates cancer rates are tied to fallout exposure. In this case, the state faile d to even consider scientific findings that have been on the books for more than a decade. “The third national cancer survey published in 1983 shows spikes of thyroid cancer in a number of hot counties (in Missouri),” says Miller. “It also shows spikes o f leukemia in a number of the hot counties, as well as, bone cancer.”

Missouri has the dubious distinction of having more than two dozen counties among the 200 nationwide that were the most heavily contaminated by nuclear fallout, according to the NCI s tudy. The majority of the effected counties are in the northeast quadrant of the state, where Miller was born and raised.

“In 1968, my father, who was a tax collector for Monroe Co. (Mo.), which is one of the hot zones, noticed there was a high level of cancer in one particular part of the county,” says Miller. After joining the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the early 1970s, Miller himself had an opportunity to further investigate his father’s observations. He too foun d what appeared to be extraordinary numbers of cancer cases in Monroe County, and he subsequently informed epidemiologists at the University of Missouri. “This was 1975 and I haven’t heard from them since,” says Miller. A year later Miller’s father died of lung cancer.

Miller’s OSHA career next took him to Texas, where he began investigating a cluster of rare brain cancers at a Union Carbide chemical plant in Houston. When he attempted expand his investigation to a nearby Dow chemical facility, the Reagan administration called a halt to it and began shredding documents. The OSHA office where he worked was ultimately closed. It was during this period that a public health official suggested to him that the pocket of brain cancer cases in Houston may h ave been the result of nuclear fallout. When he looked into it, Miller did indeed discover a correlation between fallout patterns and brain cancer clusters in both Texas and Kentucky. His extensive research finally led him to write the book on the subje ct.

Currently, Miller operates a private environmental consulting firm in Houston that investigates toxic chemical contamination. He is also the author of a novel that is set in the nuclear fallout era.

The reasoning that led to mass radiation exposure is stranger than fiction, however. “They did it because they could,” says Miller of the government’s nuclear testing program. “I think they’re mistaken impression was that it was for the greater good. At the time, they thought that if we set off these bombs, if we caused hazards across the country, we may in some way be protecting the U.S. from possible attack by the Soviets. … (But) The Soviets didn’t even have an aircraft that could make it to the U.S. and back at that time,” says Miller.

“I be lieve the feds originally caused this problem, the AEC, specifically,” he adds. “It dosed Missouri with radioactive fallout. Now it’s up to the federal government to help Missouri out in terms of education programs and possibly compensation for medical c are for particular types of illnesses that are known to be associated with fallout. I believe the first order of business is to introduce a resolution that would ask for this additional funding. I would think that the representatives from the good state of Missouri would be the ones to do that.”

Over the Dump

St. Louisans talked back to the Department of Energy about nuclear waste last Thursday. But were the feds really listening?

by Richard Byrne Jr.

The Riverfront Times, Dec. 12, 1990

The Department of Energy came to praise nuclear waste and to bury it.

Well, OK. It’s already buried there. Close to 2.5 million cubic yards of low-level radioactive waste, scattered at three main sites in North St. Louis City and County.

It’s no news that the waste is here, and it was hardly a shock that 200 angry St. Louisans showed up Thursday at a ballroom in the Clayton Holiday Inn to tell the feds they didn’t want the stuff. What’s eye-opening is the leisurely pace at which the DOE wants to clean it up.

The DOE greeted suggestions that the United States stop producing nuclear waste and start cleaning it up with polite nods. After all, as DOE Deputy Assistant Director of Environmental Restoration John Baublitz stressed, the purpose of the hearing was to gather testimony on national strategies for cleaning up waste.

The atmosphere of the hearing was geared to minimize possible conflict. There was no give-and-take between the feds and those who testified. No arguments. Few, if any, tirades.

To further everyone’s “knowledge” of nuclear issues, a booth outside the ballroom stressed the benefits of nuclear material. There were pictures of astronauts. There were two cartons of strawberries — one zapped, one not zapped. (Which do you think looked better?) There were pictures of industrial and medical uses of radiation.

And then there was the “Radiation Quiz that also had a place on the booth.

One question was” Who receives more radiation exposure in a day? Underneath there were pictures of a nuclear worker and a skier.

Another question read: Which would you rather have drive past your home? This time there were a nuclear materials truck and a fuel truck.

There was even a “true or false” question: Radioactive materials have the best safety record of all hazardous materials shipped in the last 40 years.

If you haven’t guessed already, the answers are the skier, the nuke truck and “true.”

The questions, of course, are skewed. No one skis everyday, and radiation from the sun doesn’t seep into the water table. It isn’t often that petroleum trucks whiz by our homes. And 40 years isn’t that long a track record for the shipment of low-level nuclear waste.

Local activist Kay Drey called the quiz an outrage.

“They want to belittle low-level waste,” Drey says. “Low level waste is a term created by a genius on Madison Avenue. Some low-level waste can only be handled by remote control. To compare it to garbage is absurd. Volume is not the same as hazard.”

But there are people in the St. Louis area who live near and breathe the radioactive stuff. A generation of children in Berkeley played softball on a contaminated site. People like Gilda Evans, who brought her child — stricken with leukemia — to the microphone to testify with her.

“I live in cancer alley,” says Evans, who lives a few blocks from two sites. “How long are any of us going to be here with that stuff?”

Mel Carnahan was emphatic in stressing that hazard in our locality.

“No other metropolitan area in the nation has to contend with a radioactive-waste problem as potentially threatening as the one facing St. Louis,” the lieutenant governor said.

“2.5 million cubic yards of radioactive waste are stored by the United States Department of Energy (USDOE) in the St. Louis area. This is unacceptable in such a high population density.”

You might recognize some of the people who testified: Carnahan, County Executive-elect Buzz Westfall, Ald. Mary Ross (D-5), County Councilman John Shear (D-1). But there were a lot of people you wouldn’t recognize — mothers, students, teachers, businessmen.

Almost all of them had the same thing to say:

Don’t make any more waste. Get the waste that’s here in St. Louis cleaned up.

We’ve had nuclear waste in St. Louis since there was nuclear waste to have.

Back in the early 1940s, when the brilliant minds that came up with America’s atomic weapons program — the Manhattan Project — wanted to process the uranium and thorium needed for the bomb, they came to Mallinckrodt Chemical Works right here in St. Louis. In fact, the first nuclear waste for the Atomic Age was generated in the plant at Broadway and Destrahan.

In 1946, the War Department took over 21.7 acres of land near Lambert Airport through condemnation proceedings, and directed Mallinckrodt to store the hazardous byproducts of processed uranium and thorium there. Twenty years later, some of the waste was transported to a site on Latty Avenue in Hazelwood. Then in 1973, the airport site was deeded (through a quit claim deed) back to the city, after undergoing remediation that included a foot of clean dirt being poured on top of the wastes. The city was to use it as a police-training center.

Five years later, the Department of Energy sent out a news release saying that 26 sites — including the airport site and the Mallinckrodt site — required some form of remedial action.

Both were placed under the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) in 1983 to be cleaned up.

Eight years later, it’s still sitting there. And it’s growing.

“In 1977, there was 50,000 cubic yards on contamination at Mallinckrodt,” says Drey, the most knowledgeable and passionate opponent of turning St. Louis into a dumping ground for radioactive waste. “In 1990, the latest estimates say 288,000 cubic yards of contamination, and that’s not including the buildings.”

The fight to get the sites cleaned up has lurched forward and back over the last eight years. The city’s Board of Aldermen voted unanimously in 1988 to ask the DOE to find a different place for the wastes. The Environmental Protection Agency placed the sites on Superfund, with the power to charge the owners of the land for cleanup costs. The Board of Aldermen then narrowly voted in January with the strong support of Mayor Schoemehl to donate 82 acres of land near Lambert to the DOE in exchange for indemnification against the costs of cleaning up the airport site. This would in effect, give the DOE carte blanche to “remediate on-site.” — in other words, to turn the place into a permanent storage site for the wastes with a practically eternal half-life.

Legislation introduced last year by Rep. Jack Buechner to get the wastes moved out of an urban area died in committee, and the EPA and DOE have entered into a Federal Facility Agreement that may or may not result in an on-site remediation of the wastes at Mallinckrodt, Latty Avenue and the airport site. A decision is not expected on that until 1994 at the earliest.

If a decision is handed down on the disposal of the radioactive waste at these sites in 1994, it will mean that 16 years will have elapsed since the feds first acknowledged the problem.

The 13 years that have elapsed so far have made a number of folks hopping mad, and they didn’t waste the opportunity to tell the DOE last Thursday night.

The hearing was not on St. Louis’ waste specifically, but on a DOE proposal to clean up contaminated sites in a five-year period. The Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (or PEIS) was up for one of its two public-comment sessions, but St. Louisans were more interested in specific and immediate solutions. And as three representatives of the federal agency sat at a folding table, members of the crowd stepped up to the microphone and let the DOE in on some of the solutions they had in mind.

“The federal government is responsible for bringing this waste to St. Louis,” said Ald. Mary Ross. “They’re the only party technically and financially capable of cleaning them up.”

Ross also mentioned the strong votes against the permanent storage of radioactive wastes in the November referendums: 85 percent of the city’s voters expressed their wish that the radioactive wastes scattered throughout the northern part of the metropolitan area be taken elsewhere.

“The ballot spoke strongly,” Ross insisted. “The DOE is a powerful organization. You can encourage our congressmen not only to remove these wastes, but to appropriate the funds to do it.”

Bill Ramsey of the American Friends Service Committee stressed how the citizens had been kept in the dark about the nuclear policy of the United States.

“The U.S. government never consulted its citizens,” Ramsey said. “We need public discussion and public debate.” Later in his statement, Ramsey urged the DOE to “take the money we’re saving on weapons and use that money to clean up these communities.

Drey spoke of the nation’s energy policy and the clean-up process as “the emperor’s new clothes.”

“We still don’t know how to neutralize these wastes,” Drey said, urging the government to celebrate the first half-century of the Nuclear Age — due to arrive in 1992 — with a moratorium on the production of nuclear arms and waste.

Though there is a strong “not in my backyard” strain to the anti-waste sentiment that the DOE heard last Thursday, Drey prefers to think of it as a “not anybody’s backyard” movement.

“It’s not impossible to get it cleaned up,” Drey says, citing the government’s rapid cleanup of low-level waste near Salt Lake City. “We cannot leave it where it is.”

Sister Cities?

St. Louis Shares its nuclear waste — but not a lawsuit — with a Colorado town

by Richard Byrne Jr.

The Riverfront Times, July 24, 1991

Canon City, Colo., and St. Louis have a lot in common. A lot of radioactive waste, that is.

For the most part, it’s the same waste. Much of Canon City’s waste came from materials piled up in St. Louis during the 1940s and 1950s.

Like St. Louis’ nuclear waste, Canon City’s waste was moved to its current resting place a true estimate of the dangers to the public.

Like St. Louis’ nuclear waste, it’s creating fear — and perhaps illness — in those unfortunate enough to live near the Cotter Mill processing plant in Canon City.

Unlike St. Louis’ reaction to the waste, the folks in Canon City recently filed a class action suit.

It’s a suit that makes some startling allegations:

*Radioactive waste was carelessly shipped and spilled on the journey from St. Louis to Canon City. One carload of radioactive material was, the suit claims, “lost.”

*Traces of the waste from the uranium-processing plant near Canon City have been found in Arkansas River.

*The company that runs the plant — Cotter Corporation — has a long history of failing to meet state guidelines for the processing and storage of radioactive materials.

Cotter also had a hand in St. Louis’ radioactive contamination as well, when unbeknownst to regulators, it abandoned 8,700 tons of radioactive materials too weak to be reprocessed in the West Lake Landfill in St. Louis County at a depth of only three feet.

Can we learn something from the folks in Canon City?

In the past few years, St. Louisans have become acquainted with their nuclear waste. It’s about time, too. For years, St. Louis’ role in the dawning of the nuclear age and the risks associated with it were either underestimated, glossed over or, worse yet, kept secret.

But even now, as the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) circulates its draft cleanup plans for the downtown Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, and as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issues a report calling the St. Louis Airport site (SLAPS) and Latty Avenue sites a “potential public health concern,” St. Louisans aren’t moving to gain significant input into the cleanup plans.

The residents of Canon City have taken their battle to court and sued the processors (Cotter Corporation and its parent company Commonwealth Edison) who brought the St. Louis

Airport Cakes” to their town and the two railroad companies (Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe and Santa Fe Pacific) who shipped it there.

the plaintiffs recently filed their fourth amended complaint in federal district court in Colorado.

“What we’re trying to do here is to get these companies to step forward and take care of their responsibilities,” says Lynn Boughton, a Canon City resident and one of the leading parties in the lawsuit.

The suit, which seeks a half-billion dollars in damages, charges the companies with , among other things, “negligence,” “willful and wanton conduct,” and “outrageous conduct.” The suit cites health risks to area residents, a precipitous drop in property values and the inaction of the defendants, even to this day, to take measures to improve the situation.

“No cleanup’s been undertaken yet,” Boughton says angrily. “Even after our suit’s brought all this to light. The only thing that’s happened is that (Cotter) has fenced the area.”

Cotter Corporation did not respond to RFT calls, but the lawsuit says that in a deposition conducted in February of this year, Cotter President (and Commonwealth Vice President) George Rifakes denied that there are carcinogenic materials at Cotter Mill.

The history of Canon City’s waste is inextricably tangled with St. Louis’ nuclear history — a history as long as the nuclear age itself.

In fact, the radioactive material that ended up in Canon city also resides at all four of St. Louis’ waste sites. The was was originally generated by the processing of uranium ores at the downtown Mallinckrodt plant from 1946 to 1956, and was stored at SLAPS for another 10 years.

In 1966 the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) the precursor to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), sold the residues to Continental Mining and Milling Corporation for $126,000.

Continental moved the materials to their site at 9200 Latty Ave. in Hazelwood. It was during this move that the haul routes along which the waste was moved were contaminated as well.

“The trucks that moved it weren’t covered or wetted,” says DOE spokeperson David Adler. “This move is what caused the haul-route contamination.

The stuff that Continental moved to Latty Avenue was residue from some of the highest-grade uranium available in the early 1940s — imported to the United States from the Belgian Congo.

“These materials were pretty hot stuff,” says local activist Kay Drey. It’s all the stuff that we still have out there. “

Continental went bankrupt a few years later, and that’s where Cotter stepped in, buying the residues, or raffinates, in order to dry them and ship them to its plant in Colorado to extract the remaining uranium. Cotter shipped these residues by rail to Canon City between 1970 and 1973.

According to the lawsuit, Cotter’s shipping [of the waste] was a disaster. Two of the railroad sites used to unload the raffinates are contaminated with hazardous radioactive waste. The lawsuit claims that is documentation of spillage of materials along the railroad tracks and that one “entire carload of uranium is unaccounted for.”

The suit also claims that public access to these sites was never restricted and that placards warning of radioactive material were never placed on the site.

If you think that’s bad, however, it’s nothing compared to what the lawsuit claims happened at Cotter Mill itself. The lawsuit claims that Cotter didn’t have a license to process the raffinates they shipped to Colorado and that two-thirds of the material was processed before Cotter notified the state. The suit also claims that some of the raffinates brought to Colorado were never processed and sit on the grounds, without cover and exposed to the elements. (Much of the St. Louis waste is covered with a tarpaulin, which has occasionally blown off.

The raffinates that were processed, the suit claims, have seeped into the groundwater, making their way to the nearby Arkansas River.

`Boughton, a chemist at Cotter until 1979, says that the company didn’t even tell its employees about the danger.

“No one told us what the isotopic content of this material was,” Boughton says. “We had processed a lot of the material when it came back to us through a lab that was following the material.”

What the material was full of, the suit claims, is thorium-230 and protactinium-231. Both are highly dangerous wastes, with measurable concentrations also present in the St. Louis’ piles. Boughton was later diagnosed as having lymphoma cancer — a cancer associated with thorium-230.

The lawsuit also lists a long series of citations of Cotter Mill — by the AEC and the state of Colorado — for non-compliance with license regulations, citiations dating back to 1959.

St. Louisans can feel bad for the residents of Canon City. they can even regret that it’s waste form the St. Louis area that has wreaked such havoc on their lives and property. But what relevance does Canon City case have for St. Louisans?

First, of course, is Cotter’s illegal dumping of 8,700 tons of radioactive waste at West Lake Landfill, near Earth City. A History of the St. Louis Airport Uranium Residues, prepared by Washington, D.C.’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IEER), claims that Cotter dumped the waste “without the knowledge or approval…”

The IEER report also claims that the NRC has urged Cotter to “apply promptly for a license authorizing remediation of the radioactive waste in the West Lake Landfill.” The reports also says that Cotter has not yet taken any remeidal action.

But lawyers and activists insist that it’s not just the waste here in St. Louis that should turn local residents eyes to the Colorado lawsuit.

Louise Roselle, a Cincinnati lawyers who is aiding in the Colorado lawsuit, claims that the Colorado suit “is part of a growing amount of litigation in this country by residents around hazardous facilities.”

Kay Drey says that the Colorado suit is also interesting because of the research that’s being done on the materials that are contaminating Canon City.

“That’s basically the same stuff we have here,” Drey says. It’s just more splattered here — at a couple different sites.”

It’s the splattering effect in St. Louis that makes these sites more difficult to characterize and to remediate. The DOE is in the middle of the process of remediating a number of St. Louis sites — particularly SLAPS, Latty Avenue, and Mallinckrodt. But a record of decision —the DOE and Environmental Protection Agency’s official decision on what to do with St. Louis’ waste — is not due until 1994.

Drey says that St. Louisans need to keep the pressure on and take an interest in their nuclear waste.

“We need to let our leaders know that we want this stuff out of here,” Drey says. “What’s interesting about this lawsuit is that (Canon City) is looking into what it casn do with its waste.”