St. Louisans talked back to the Department of Energy about nuclear waste last Thursday. But were the feds really listening?

by Richard Byrne Jr.

The Riverfront Times, Dec. 12, 1990

The Department of Energy came to praise nuclear waste and to bury it.

Well, OK. It’s already buried there. Close to 2.5 million cubic yards of low-level radioactive waste, scattered at three main sites in North St. Louis City and County.

It’s no news that the waste is here, and it was hardly a shock that 200 angry St. Louisans showed up Thursday at a ballroom in the Clayton Holiday Inn to tell the feds they didn’t want the stuff. What’s eye-opening is the leisurely pace at which the DOE wants to clean it up.

The DOE greeted suggestions that the United States stop producing nuclear waste and start cleaning it up with polite nods. After all, as DOE Deputy Assistant Director of Environmental Restoration John Baublitz stressed, the purpose of the hearing was to gather testimony on national strategies for cleaning up waste.

The atmosphere of the hearing was geared to minimize possible conflict. There was no give-and-take between the feds and those who testified. No arguments. Few, if any, tirades.

To further everyone’s “knowledge” of nuclear issues, a booth outside the ballroom stressed the benefits of nuclear material. There were pictures of astronauts. There were two cartons of strawberries — one zapped, one not zapped. (Which do you think looked better?) There were pictures of industrial and medical uses of radiation.

And then there was the “Radiation Quiz that also had a place on the booth.

One question was” Who receives more radiation exposure in a day? Underneath there were pictures of a nuclear worker and a skier.

Another question read: Which would you rather have drive past your home? This time there were a nuclear materials truck and a fuel truck.

There was even a “true or false” question: Radioactive materials have the best safety record of all hazardous materials shipped in the last 40 years.

If you haven’t guessed already, the answers are the skier, the nuke truck and “true.”

The questions, of course, are skewed. No one skis everyday, and radiation from the sun doesn’t seep into the water table. It isn’t often that petroleum trucks whiz by our homes. And 40 years isn’t that long a track record for the shipment of low-level nuclear waste.

Local activist Kay Drey called the quiz an outrage.

“They want to belittle low-level waste,” Drey says. “Low level waste is a term created by a genius on Madison Avenue. Some low-level waste can only be handled by remote control. To compare it to garbage is absurd. Volume is not the same as hazard.”

But there are people in the St. Louis area who live near and breathe the radioactive stuff. A generation of children in Berkeley played softball on a contaminated site. People like Gilda Evans, who brought her child — stricken with leukemia — to the microphone to testify with her.

“I live in cancer alley,” says Evans, who lives a few blocks from two sites. “How long are any of us going to be here with that stuff?”

Mel Carnahan was emphatic in stressing that hazard in our locality.

“No other metropolitan area in the nation has to contend with a radioactive-waste problem as potentially threatening as the one facing St. Louis,” the lieutenant governor said.

“2.5 million cubic yards of radioactive waste are stored by the United States Department of Energy (USDOE) in the St. Louis area. This is unacceptable in such a high population density.”

You might recognize some of the people who testified: Carnahan, County Executive-elect Buzz Westfall, Ald. Mary Ross (D-5), County Councilman John Shear (D-1). But there were a lot of people you wouldn’t recognize — mothers, students, teachers, businessmen.

Almost all of them had the same thing to say:

Don’t make any more waste. Get the waste that’s here in St. Louis cleaned up.

We’ve had nuclear waste in St. Louis since there was nuclear waste to have.

Back in the early 1940s, when the brilliant minds that came up with America’s atomic weapons program — the Manhattan Project — wanted to process the uranium and thorium needed for the bomb, they came to Mallinckrodt Chemical Works right here in St. Louis. In fact, the first nuclear waste for the Atomic Age was generated in the plant at Broadway and Destrahan.

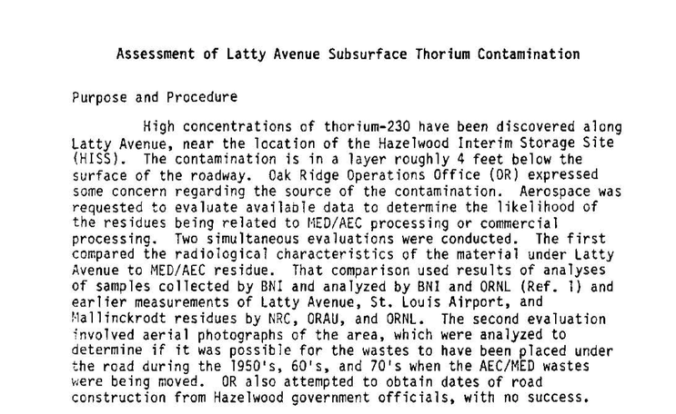

In 1946, the War Department took over 21.7 acres of land near Lambert Airport through condemnation proceedings, and directed Mallinckrodt to store the hazardous byproducts of processed uranium and thorium there. Twenty years later, some of the waste was transported to a site on Latty Avenue in Hazelwood. Then in 1973, the airport site was deeded (through a quit claim deed) back to the city, after undergoing remediation that included a foot of clean dirt being poured on top of the wastes. The city was to use it as a police-training center.

Five years later, the Department of Energy sent out a news release saying that 26 sites — including the airport site and the Mallinckrodt site — required some form of remedial action.

Both were placed under the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) in 1983 to be cleaned up.

Eight years later, it’s still sitting there. And it’s growing.

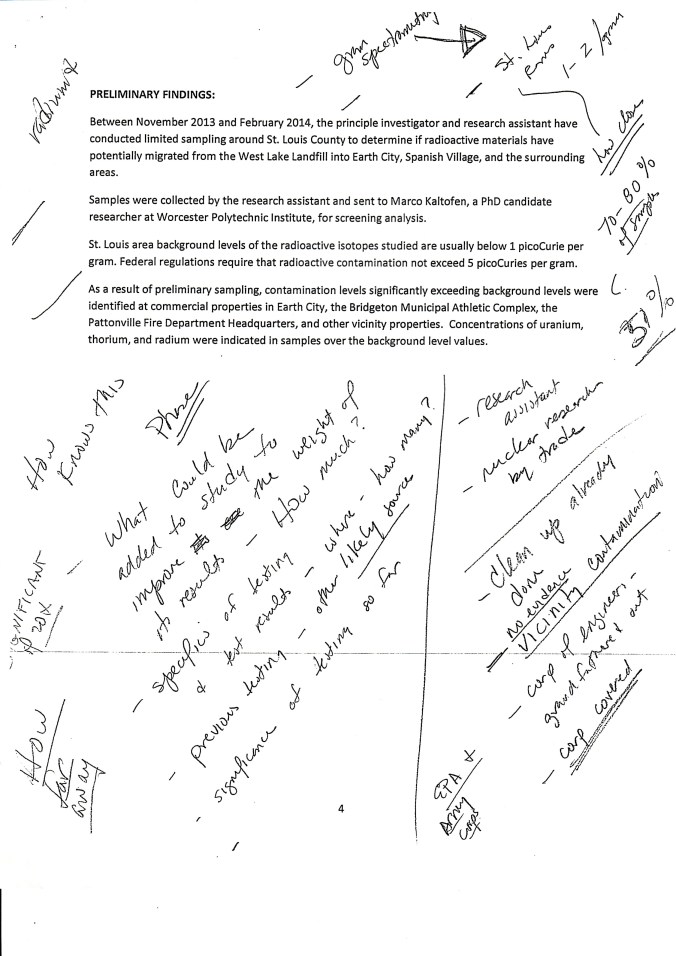

“In 1977, there was 50,000 cubic yards on contamination at Mallinckrodt,” says Drey, the most knowledgeable and passionate opponent of turning St. Louis into a dumping ground for radioactive waste. “In 1990, the latest estimates say 288,000 cubic yards of contamination, and that’s not including the buildings.”

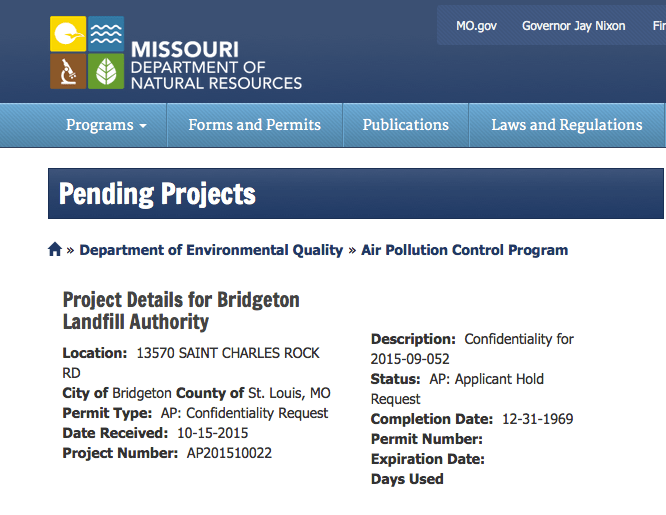

The fight to get the sites cleaned up has lurched forward and back over the last eight years. The city’s Board of Aldermen voted unanimously in 1988 to ask the DOE to find a different place for the wastes. The Environmental Protection Agency placed the sites on Superfund, with the power to charge the owners of the land for cleanup costs. The Board of Aldermen then narrowly voted in January with the strong support of Mayor Schoemehl to donate 82 acres of land near Lambert to the DOE in exchange for indemnification against the costs of cleaning up the airport site. This would in effect, give the DOE carte blanche to “remediate on-site.” — in other words, to turn the place into a permanent storage site for the wastes with a practically eternal half-life.

Legislation introduced last year by Rep. Jack Buechner to get the wastes moved out of an urban area died in committee, and the EPA and DOE have entered into a Federal Facility Agreement that may or may not result in an on-site remediation of the wastes at Mallinckrodt, Latty Avenue and the airport site. A decision is not expected on that until 1994 at the earliest.

If a decision is handed down on the disposal of the radioactive waste at these sites in 1994, it will mean that 16 years will have elapsed since the feds first acknowledged the problem.

The 13 years that have elapsed so far have made a number of folks hopping mad, and they didn’t waste the opportunity to tell the DOE last Thursday night.

The hearing was not on St. Louis’ waste specifically, but on a DOE proposal to clean up contaminated sites in a five-year period. The Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (or PEIS) was up for one of its two public-comment sessions, but St. Louisans were more interested in specific and immediate solutions. And as three representatives of the federal agency sat at a folding table, members of the crowd stepped up to the microphone and let the DOE in on some of the solutions they had in mind.

“The federal government is responsible for bringing this waste to St. Louis,” said Ald. Mary Ross. “They’re the only party technically and financially capable of cleaning them up.”

Ross also mentioned the strong votes against the permanent storage of radioactive wastes in the November referendums: 85 percent of the city’s voters expressed their wish that the radioactive wastes scattered throughout the northern part of the metropolitan area be taken elsewhere.

“The ballot spoke strongly,” Ross insisted. “The DOE is a powerful organization. You can encourage our congressmen not only to remove these wastes, but to appropriate the funds to do it.”

Bill Ramsey of the American Friends Service Committee stressed how the citizens had been kept in the dark about the nuclear policy of the United States.

“The U.S. government never consulted its citizens,” Ramsey said. “We need public discussion and public debate.” Later in his statement, Ramsey urged the DOE to “take the money we’re saving on weapons and use that money to clean up these communities.

Drey spoke of the nation’s energy policy and the clean-up process as “the emperor’s new clothes.”

“We still don’t know how to neutralize these wastes,” Drey said, urging the government to celebrate the first half-century of the Nuclear Age — due to arrive in 1992 — with a moratorium on the production of nuclear arms and waste.

Though there is a strong “not in my backyard” strain to the anti-waste sentiment that the DOE heard last Thursday, Drey prefers to think of it as a “not anybody’s backyard” movement.

“It’s not impossible to get it cleaned up,” Drey says, citing the government’s rapid cleanup of low-level waste near Salt Lake City. “We cannot leave it where it is.”