In 2005, the city of St. Louis paid the owner of the Bridgeton Landfill a bundle to gain control of activities at the West Lake Landfill Superfund Site on behalf of the city-owned airport. Today, the city’s role remains largely invisible even though it may ultimately determine the future of the cleanup — if it hasn’t already.

Karen Nickel of Just Moms STL introducing St. Ann alderwoman and County Council candidate Amy Poelker at a 2016 candidate forum sponsored by the organization.

Karen Nickel of Just Moms STL introducing St. Ann alderwoman and County Council candidate Amy Poelker at a 2016 candidate forum sponsored by the organization.

Since 2013, Just Moms STL, a community organization, has held monthly meetings to raise public awareness of the EPA’s West Lake Landfill Superfund Site in Bridgeton, Mo., a St. Louis suburb where nuclear waste from the Manhattan Project was illegally dumped in 1973.

At the opening of each meeting, organizers take a moment to recognize area elected officials or their representatives who are in attendance. They run the gamut of local to federal office holders: municipal councilmen, St. Louis County Council members, state legislators, representatives from the office of the St. Louis County executive, aides from all four members of the St. Louis congressional delegation.

It’s an impressive show of bi-partisan political support for citizens who are confronting this long-neglected environmental disaster.

But one seat in the room is always empty.

Noticeably missing from these gatherings — for the past four years — are representatives of the city of St. Louis or its mayor. Their absence comes despite the city’s having struck a deal with the landfill owner in 2005 that essentially allows the city to dictate operations at the former landfill forever.

The city acquired this influence in the old-fashioned way: It paid cash.

Under the 2005 agreement, which was brokered during the administration of then-Mayor Francis Slay, the city paid $400,000 to Allied Waste, the disposal company that then owned the troubled property. In return, St. Louis gained the legal authority to end operations there. The landfill was required to stop accepting trash and refrain from any further excavation. Moreover, the site owner is mandated to conform in perpetuity to the restrictive terms set forth by the city of St. Louis inside the Superfund site. The covenant between the property owner and the city is neither superseded nor negated by the EPA’s separate land use restrictions.

In short: The city controls the site.

Under the agreement, not a speck of dirt may be dug up, turned over, rearranged, or excavated without the city’s approval. The city through its St. Louis Airport Authority,— has resisted any amendment of the agreement, citing federal safety regulations.

Though negotiations to alter the ruling have dragged on for years, the impasse has been downplayed or ignored by the news media and the public at large.

The fine print in the 2005 accord stipulates that future owners of the property must abide by the same set of restrictions. This means that the restrictive covenants put in place 12 years ago now apply to Republic Services, the waste disposal company that acquired the site as part of a merger in 2008.

Republic bought into the toxic mess at the West Lake Superfund Site when it acquired Arizona-based Allied Waste, which in turn had purchased the site from Laidlaw Waste Systems in 1996. The following year, Allied Waste merged Laidlaw Waste Systems of Missouri to create a Delaware registered subsidiary — Bridgeton Landfill LLC. That’s the company that the city of St. Louis cut the deal with in 2005.

If all of this sounds confusing, it’s because it is.

But one detail is clear: Though the corporate ownership shifted, one executive’s name has been tied to the toxic landfill for 20 years: Donald Slager — the current CEO of Republic Services.

As a company officer of Allied Waste, Slager signed the 1997 merger agreement that registered Bridgeton Landfill in Delaware, a state known for its strict corporate secrecy laws.

As a company officer of Allied Waste, Slager signed the 1997 merger agreement that registered Bridgeton Landfill in Delaware, a state known for its strict corporate secrecy laws.

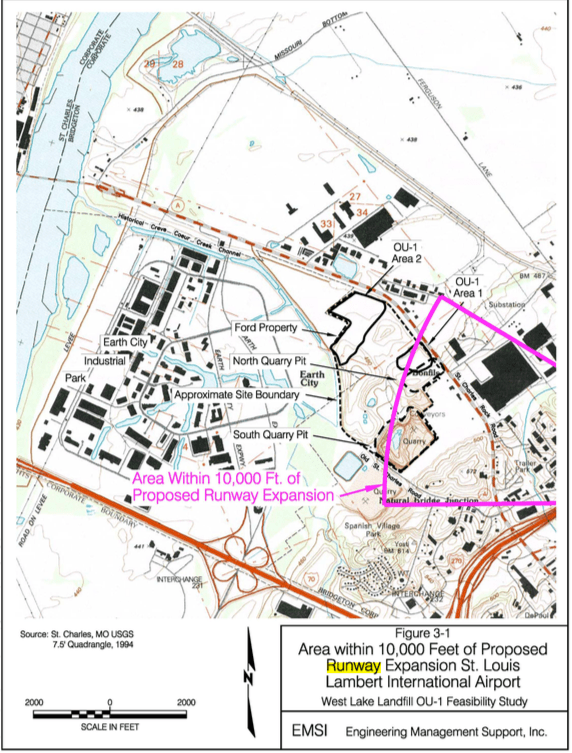

Sealing the little-known 2005 property pact with Bridgeton Landfill — known as a “negative easement” — allowed the airport authority to comply with a Federal Aviation Administration safety regulation related to flight risks posed by birds at St. Louis Lambert International Airport.

Bird strikes by commercial aircraft are fairly common and reopening the West Lake landfill could attract flocks of hungry birds. But in this case, disagreement exists as to whether the presence of birds at West Lake outweighs the hazard posed by allowing radioactive waste to continue polluting the environment.

FAA rules are focused on hazards in the sky, not on earth. So to address the winged threat, the FAA mandates that airports accommodating passenger jet service be located at least 10,000 feet from active landfills. The West Lake Superfund Site, of which the Bridgeton Landfill is a part, lies 9,100 feet from the nearest Lambert runway.

“Under the FAA regulations, the airport is responsible for ensuring proper wildlife management practices are in place for whatever mitigation is ultimately selected for the landfill,” says FAA spokeswoman Elizabeth Isham Cory. “The goal is to minimize any possibility for potential bird strikes.”

Granted that leverage, the city of St. Louis has found a way to kill two birds with one stone. It bought the negative easement ostensibly to conform with the federal regs but in so doing it acquired considerable influence over the choice of method that will ultimately be used to clean up the site.

In this case, a relatively obscure clause within a federal regulation is being used by the city to block plans to either contain the radioactive materials at West Lake or — the preferred choice of many community members — remove them. As a result, the air safety regulation presents a fixed impediment to the EPA’s efforts to address the long-term goal of protecting human health and the environment at the site.

The airport authority advocates capping the waste in place — the cheapest option. By no small coincidence, this remedy is also supported by Republic Services, the landfill’s owner.

In its 2008 record of decision, the EPA also favored leaving the waste in place and capping it, but the agency is now reconsidering the plan after encountering public opposition. In the interim, the agency acknowledged that seepage from the unlined landfill is contaminating groundwater at the site — which is located in a floodplain, 1 mile from the Missouri River.

The estimated cost of capping the landfill with dirt and gravel is $40 million. Removing the waste could cost 10 times as much. Though capping may save money, it merely buries the problem, and only ensures further contamination of the aquifer. Nor does it do anything to snuff out the underground fire that’s smoldering at the site.

The dilemma that no government source seems to want to talk about is whether the EPA’s mission to protect human health and the environment should take a backseat to a FAA reg that may or may not help ensure safety of air travelers. The EPA, St. Louis Airport Authority, and office of Lyda Krewson, the new St. Louis mayor, were all asked to comment and declined.

Enforcement of the FAA regulation on preventing bird strikes involves yet another federal agency, the U.S Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services. Agents from that agency were spotted inspecting the site earlier this spring. A spokesman for the agency declined comment.

A USDA vehicle was seen at the West Lake site on April 13. (photo by Robbin Ellison Dailey.)

A USDA vehicle was seen at the West Lake site on April 13. (photo by Robbin Ellison Dailey.)

Previous public statements by the airport director have indicated that the airport’s deal with the property owner has cut down the number of bird strikes at Lambert and that for this reason the 2005 agreement should not be amended or nullified.

In a five-page letter written by airport director Rhonda Hamm-Niebruegge to then–EPA West Lake Landfill Superfund Site project manager Dan Gravatt in September 2010, she acknowledged the seriousness of the presence of uncontrolled radioactive waste at the site but said that any action taken must not compromise the city’s obligation to protect public safety.

“The USDA Wildlife Service has advised the City that uncovered radiologically-impacted municipal waste at the West Lake Landfill will serve as a food attractant for a variety of bird species and increase the risk of bird/aircraft strikes at the airport,” Hamm- Niebruegge wrote.

The airport director cited 600-plus incidences of bird strikes recorded at Lambert since the 1990s. After implementation of the 2005 agreement, she said, there was a marked reduction in such occurrences. The city again opposed digging at the landfill in 2014, when the EPA considered building a barrier to halt the advance of the underground fire burning in the direction of the radioactive waste. In this case, Hamm-Niebruegge and Jeff Rainford, chief of staff for Mayor Slay, co-signed a letter nixing any digging at the site for the same reasons cited four years earlier.

The ornithological suspects in the kamikaze flights have reportedly included vultures, geese, hawks, gulls, owls, and the lowly pigeon.

The safety of 13 million travelers flying in and out of Lambert each year each year was at stake, according to the airport director’s 2010 missive. It is unclear from the letter, however, whether any casualties have resulted from these mismatched encounters besides those suffered by our fine feathered friends.

The safety of 13 million travelers flying in and out of Lambert each year each year was at stake, according to the airport director’s 2010 missive. It is unclear from the letter, however, whether any casualties have resulted from these mismatched encounters besides those suffered by our fine feathered friends.

“The plans shared with the Airport … indicate that any isolation barrier alternative will result in substantial amounts of putrescible wastes being excavated and managed at the landfill over a long indeterminate period of time. Due to the amount of putrescible waste being excavated and the lengthy period of the project, the Airport believes there is potential for a bird hazard to develop from activities associated with the construction of an isolation barrier,” Hamm-Niebruegge and Rainford wrote.

The barrier was never built, and the fire is still burning.

Some think the airport’s stance is for the birds.

Critics include former Missouri state Rep. Bill Otto, whose 70th District included Bridgeton and part of St. Charles County. Otto is a retired air traffic controller and a founding member of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association. He worked for decades at Lambert when the airport was a hub for TWA and American Airlines. In his opinion, excavating the landfill to remove the radioactive and chemical contaminants does not pose a realistic safety hazard, and the fear of bird strikes is unwarranted.

“It’s simply not true. It is not a factor,” Otto says. He bases his belief on more than 20 years of professional experience. In his long tenure at Lambert, Otto says, the airport never experienced problems with birds resulting from landfill operations. At that time, the dump was open for business and accepting all manner of household refuse and garbage, as well as toxic waste. He adds that the airport then handled 75 percent greater air traffic volume.

Even if birds suddenly became an issue during the cleanup, Otto believes air traffic controllers could simply change traffic patterns to avoid the risks. Moreover, the cleanup plan itself could include measures to help keep birds from posing a hazard. “There are all kinds of ways to deal with it on a long-term or short-term basis,” Otto says.

Otto suspects that the real reason for the bird flap is two-legged interference on the ground. “Republic Services [the landfill owner] is pushing the airport, using the potential for bird activities as a reason it shouldn’t be excavated,” he says. “Honestly, I think it’s a political maneuver on their part.” Otto sees cleaning up the landfill as the top priority: “The needs of the community are greater than the traffic flow at the airport.”

Russ Knocke, the chief spokesman for Republic Services, did not return a call requesting a response to Otto’s comments.

The EPA’s own National Remedy Review Board concurs with Otto’s assessment. In its 2013 review of the West Lake Superfund Site, the NRRB stated that most of the contaminated sections of the landfill are located farther than 10,000 feet from any Lambert runway.

Moreover, the NRRB asserted that bird-related problems could be handled with little difficulty. “It should be feasible to use netting or devices (e.g. moveable tent or building) for the short amount of time that would be needed to excavate or treat the RIM [radiologically impacted materials],” said the the NRRB.

Most important, the NRRB review stated that the environmental law that governs EPA Superfund sites is not restricted by the airport’s move to conform to FAA regulations. The review board, however, may only offer its opinion; it has no enforcement powers. In other words, the negative easement held by the St. Louis Airport Authority has not been overturned and remains legally binding.

Many Bridgeton residents have difficulty accepting the airport authority’s position at face value. Their doubts are based on shared history and collective memory. The distrust stems from the imposition of past FAA and EPA fiats by the city of St. Louis and its airport authority. At first glance, these events seem unrelated, but they’re part of the same long-term plan that has had a devastating overall impact on Bridgeton.

Grasping how these machinations fit together requires some understanding of the political jurisdictions that divide the St. Louis area. Bridgeton is one of more than 90 incorporated municipalities in St. Louis County. These suburban fiefdoms surround the city of St. Louis, which is itself independent from St. Louis County thanks to boundaries drawn in the late 19th century. The idea of unifying the region is the subject of perennial civic debate that has never progressed beyond the talking stage. Because of this peculiar jurisdictional arrangement, the city of St. Louis has been stymied from exerting influence over the independent incorporated municipalities in St. Louis County.

Bridgeton is the exception to that rule: The city of St. Louis owns the airport — which is located inside the Bridgeton city limits.

The deal hashed out in 2005 between the city of St. Louis and the landfill owner was originally spurred by airport expansion plans initiated in the 1990s, most notably a proposal to build a controversial billion-dollar runway. The now-completed runway project required more than 2,000 homes in Bridgeton’s Carrollton subdivision to be razed so the airport could adhere to EPA sound-abatement guidelines.

Though many Carrollton residents opposed the forced buy-out, bulldozing moved forward in a matter of years. More than 5,000 Bridgeton citizens were dislocated, and the city of St. Louis is now the absentee landlord of the abandoned property, which resembles a ghost town. The homes are gone, but vestiges of habitation still haunt the place. Ornamental trees and shrubbery dot the landscape. Grassy lawns outline where homes once stood. Light standards and utility poles provide an eerie symmetry. A living room sofa sits in the middle of one former thoroughfare.

An empty street in the abandoned Carrollton subdivision. (photo by Alison Carrick)

An empty street in the abandoned Carrollton subdivision. (photo by Alison Carrick)

Across town from Carrollton, another Bridgeton subdivision now finds itself in limbo. Residents of Spanish Village endure the stench from the underground fire at the nearby West Lake Superfund Site, their lives in a holding pattern while the EPA’s bureaucracy and the city of St. Louis wrangle over the terms of the clean up.

Robbin Ellison Dailey is one of the Spanish Village residents whose lives have been affected by the West Lake mess. Her husband Mike, who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, was recently hospitalized because of the condition. The couple, who’ve been exposed to the air pollution from the dump for years, have filed a lawsuit against the current owner of the landfill. Late last year, independent testing confirmed the presence of radiological particles in their home, and since then other homes in the subdivision have tested positive. But the EPA’s sampling of Spanish Village residences did not detect increased levels of radioactive materials. The agency says there is no reason for concern.

Not surprisingly, Dailey doesn’t trust the EPA’s findings any more than she believes the airport’s reasons for opposing excavation at the landfill.

“I think it’s the lamest excuse I have ever heard,” says Dailey. “It’s like they’re [willing] to put safety of aircraft over the safety of individuals and communities that are having to live with this problem in their midst.” There is no need to sacrifice the safety of either, in her opinion. She says that airport controllers could guide planes around the landfill, using a different flight path. “They don’t have to come in over the landfill. This bird situation is absolutely ridiculous.”

Dailey’s view seems reasonable, but decisions regarding the landfill never have been dictated by common sense or the common welfare. Instead, the priorities of powerful special interests appear to be what’s guiding policy decisions.

According to the EPA’s 2011 supplemental feasibility study: “The city’s control over the site “shall end only if and when the City of St. Louis chooses in its sole and absolute discretion to abandon its negative easement.” Persuading the airport authority to relinquish the power it holds over the site is unlikely; it has shown no sign that its position has changed. In its 2011 report, the EPA noted that the airport authority had indicated that any “excavation remedy would create risks that they could not even calculate.”

Although the airport authority has paid lip service to addressing environmental hazards at the site, the landfill’s litany of pollution problems is apparently still off its radar. Besides the underground fire, the final cleanup plan must take into account the radioactive and chemical contaminants that are known to be leaking into the aquifer in the floodplain, just a mile from the Missouri River, which provides drinking water to a large portion of the region’s population.

When asked to give the city’s position on the West Lake issue, a spokesman for newly elected St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson declined to comment. The reticence itself sends a message: It’s business as usual at City Hall.

The original version of this story incorrectly cited Laidlaw Waste Systems as the company that signed the negative easement with the St. Louis Airport Authority in 2005. That is incorrect. Allied Waste, the then-owner of the Bridgeton Landfill, agreed to the arrangement.

I watched Atomic Homefront this weekend after just searching On Demand channels for something interesting to watch. I can’t get it off my mind now. Ms. Dailey’s pleas tore at my heart. Sometimes it really feels like we’re living in a third world country. How in the world do you let something like this drag on for so many years? In the documentary she asked how could she make Thanksgiving dinner? An even better question would be which of those “officials” would be willing to eat at her home knowing now of the “reasonable levels of contamination?

Another question I am wondering about is, even if they moved somewhere else, another state entirely, what are the implications. I mean, is this stuff in their clothes, mementos, car, furniture, potted plants, sheets, blankets, dishes? Do you just get up and leave every single thing you own behind? Seriously, who’s figuring that out? I’d love to see an article hear about that. It would be terrifying to find these poor people move elsewhere [without the intention of] contaminating a new area. With levels inside their homes at 1000 times the acceptable limit, is that not a reasonable concern? That’s scary as well.

LikeLike

By the way, glad I found this blog. I’ll be following.

LikeLike